The Case for Informal Training: Why Experience Trumps the Classroom

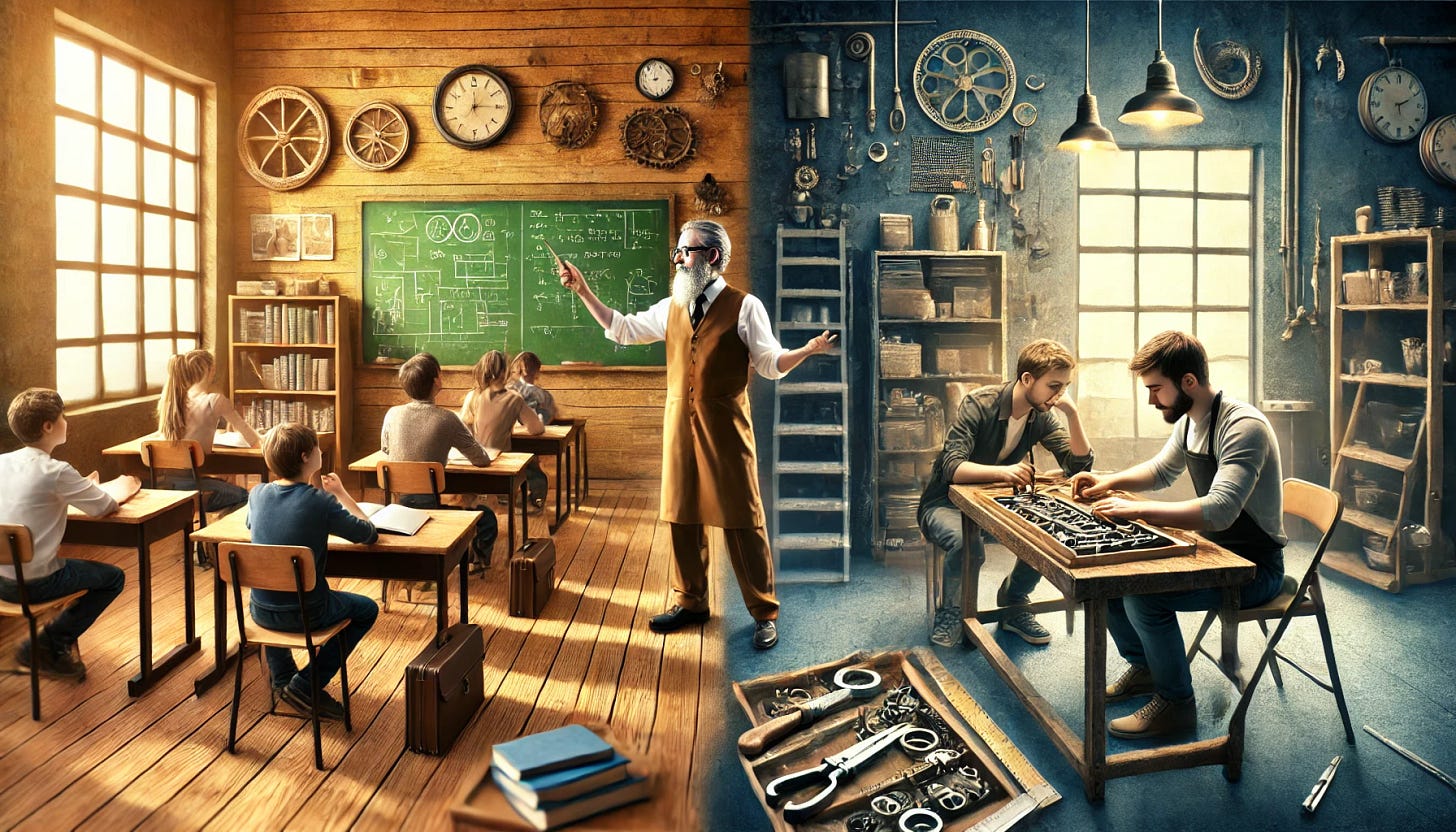

I believe that informal training offers greater value than formal training.

In my years of delivering training courses, I noticed that the most impactful learning didn’t come from PowerPoint slides or well-intentioned lectures—it emerged through real-world discussions, hands-on experience, and the exchange of knowledge among peers. While formal training has its place, particularly when required by regulations, real skill development happens in the field. That’s where workers interact with their environment, tackle challenges in real time, and apply their knowledge in ways no classroom setting can truly replicate.

When I led training sessions, my ideal group size was 8 to 12 participants, as it fostered discussion and kept the session balanced. But there were days when I’d walk into a nearly empty room, facing just one or two attendees. Their disappointment was immediate—they’d sigh, shift uncomfortably in their seats, and ask, “How long is this course going to be?”

Rather than giving them a direct answer, I’d share a story about a farmer that my mentor once recounted to me.

The Farmer and the Preacher

A farmer once went to church on Sunday morning, only to find that he was the only one in the congregation. The preacher saw this and, rather than shortening his sermon, delivered the full fire-and-brimstone message he had prepared as if the pews were packed. He spoke with passion, pouring his heart into every word, sweating from the intensity of his delivery.

At the end of the sermon, he approached the farmer and asked, "So, what did you think?"

The farmer thought for a moment and then said, "Well, preacher, I have 150 head of cattle back home. When I go out to feed them and only one cow shows up, I don’t try to cram all 150 portions of grain into that one cow."

The moral of the story? Formal training, like that sermon, should be adapted to the audience. If I had one attendee, I wasn’t going to force eight hours of material onto them. Instead, I would adjust the session to match their existing skill set, experience, and education—focusing on what they truly needed rather than delivering a one-size-fits-all lesson. In that sense, even formal training becomes somewhat informal, shaped by the people in the room.

The Problems with Formalized Training

In many industries, formal training requirements are shaped by regulatory bodies. Some training must be delivered by an approved provider, like first aid training, or follow a recognized standard—for example, operator training for lift trucks must meet the requirements set out by the Canadian Standards Association (CSA). Other training requirements are less prescriptive; regulations might simply state that workers must receive “adequate” instruction or training, leaving the definition of adequacy open to interpretation

But how do we determine if this ‘adequate training’ is actually effective?

The unfortunate truth is that the only real litmus test for whether training was adequate is in the aftermath of an accident. If a worker is severely injured or killed, investigators will ask: Did they receive proper training? If it can be proven that inadequate training contributed to the incident, then the training was deemed insufficient.

But this raises a troubling point—there are no truly universal standards for "adequate" training. The general structure of formal training follows a simple model:

Transfer of knowledge (typically through classroom instruction or online modules).

Discussion and demonstration (such as showing how a harness works).

Practical application (having workers don a harness and perform tasks).

But studies consistently show that most people retain only a fraction of what they learn in training. Within 24 hours, we forget up to 70% of the material if it’s not reinforced through practice, known as the forgetting curve. The longer we go without reinforcing new information, the more of it we lose. Within 30 days, we forgot up to 90% of what we learned. This is why refresher courses exist—not necessarily because workers need them at fixed intervals, but because the human brain discards information that isn’t regularly used.

For regulatory training, refreshers are mandated by law. But for privately offered training courses, there is no universal standard. In my experience, we often left it up to the employer to decide how often refresher training was needed. If workers weren’t regularly using a skill, they’d likely need a refresher in two years. But if they were using it daily, was that refresher really necessary?

This raises a bigger question: if 90% of formal training is forgotten within a month, yet informal, hands-on training allows for continuous reinforcement and better retention, why do we still rely so heavily on the classroom model?

Is Training the Real Culprit in Workplace Incidents?

In accident investigations, "lack of training" is often cited as a root cause. But is training truly to blame?

Workplace incidents are rarely the result of a single failure. They are complex, messy, and often involve multiple contributing factors. A worker may have received training but forgot key details, made a judgment call under pressure, or was influenced by workplace culture. Even the best training can’t account for every variable in a high-risk environment.

And yet, when an accident happens, formal training is scrutinized as if it’s the sole safeguard against risk. The reality is that training is just one piece of the puzzle. Once a worker completes a course, it’s up to supervisors and experienced colleagues to ensure that the knowledge is applied correctly in the field. In that sense, formal training is only the beginning—the real learning happens on the job.

This leads to the real heart of the issue: informal training is where the real value lies.

The Power of Informal Training

If we look at how people truly learn complex skills, we see that most of it happens outside of the classroom. Learning is an ongoing process—one that is reinforced through observation, practice, and mentorship.

One of the best examples of this is how we learn to drive.

Most people don’t learn to drive through formal courses alone. Instead, they learn informally—through their parents, older siblings, or trusted adults. Many teenagers get their first taste of driving on quiet country roads, away from traffic and the watchful eyes of law enforcement.

How does this training happen? It follows the same instinctive learning model that humans have used for generations:

Discussion – Parents explain the basics of how a car works. They might pop the hood, show where the engine is, and discuss things like steering, brakes, and acceleration.

Demonstration – The child observes their parent driving, listening to their instructions. Parents might even narrate their actions: "See that stop sign? I’m slowing down early because the road is icy."

Practice – The child gets behind the wheel, feeling the responsiveness of the accelerator, the resistance of the brakes, and the turn radius of the steering wheel—all under the careful supervision of an experienced driver.

Over time, the training progresses to more complex tasks—driving in traffic, reversing, handling intersections. Eventually, the teenager takes their driver’s test, a formal evaluation of their skills. But their real training didn’t come from that final test—it came from hours of informal practice.

The Role of Experience in Learning

As Gerald Wilde argues in Target Risk, greater risk—and the acceptance of it—is an unavoidable part of gaining experience. Experience must be bought; accidents are part of the price. No one learns to play the violin perfectly without making mistakes, just as no one learns to drive without close calls.

Wilde further explains that a novice driver’s accident rate isn’t solely due to their inexperience—it’s due to the mix of experienced and inexperienced drivers on the road. If only novice drivers were on the road together, their accident rate might actually be lower. The problem isn’t simply that they lack experience; it’s that they are learning in an unpredictable, fast-moving environment dominated by those who already have experience.

The same logic applies to workplace training. Workers don’t become competent because they sat through a PowerPoint presentation—they become competent through exposure to real tasks, real risks, and real experiences. Mistakes will happen, but those mistakes are part of the learning process.

And yet, modern training models are built around the idea that mistakes can be eliminated through rigid instruction. This ignores the reality that skills are developed through trial, error, and gradual improvement. Just as a musician can’t master an instrument without playing it, a worker can’t truly develop expertise without engaging in hands-on, real-world practice.

Conclusion: The Need for a Shift in Training Philosophy

The paradox of workplace training is clear: some of the riskiest tasks in life—like driving—are largely learned informally, while relatively lower-risk workplace tasks are subjected to rigid, formalized instruction.

Why?

Part of the reason is liability—employers need documentation proving that training was provided. But there’s also a financial and bureaucratic incentive at play. Industries that profit from training certifications push for regulatory requirements that reinforce their business model. And regulators, rather than trusting in the natural process of skill development, lean toward compliance-based training over competency-based training.

But true learning doesn’t happen in a classroom. It happens in the field, through mentorship, observation, and repetition. It happens in moments of uncertainty, when a worker must assess a situation and apply their skills in real time. And it happens through experience—both good and bad—because, as Wilde suggests, there is no royal road to learning.

If we want workers to be truly competent, we need to rethink our reliance on rigid training structures and put more trust in the power of informal, experience-driven learning. Because at the end of the day, the best training isn’t about checking a regulatory box—it’s about ensuring that workers can actually do the job safely, effectively, and with confidence.